David Sylvester, The Human Body, 1998 (London, Hayward Gallery, Francis Bacon: The Human Body, 1998). Bacon has lately survived exposure to two vast museum spaces that could have been killers ‑ the Centre Pompidou in Paris and the Haus der Kunst in Munich. They brought out a grandeur in the work that had tended to be less manifest than its expressiveness and its vitality. Some paintings seemed to possess a Matissean severity and serenity that had not previously been suspected. Canvases hung in the two daylit areas of the Paris showing had a vibrancy that made Bacon look as much a colourist as a dramatist: the grisaille paintings of the late 1940s and early Fifties had a hushed lyricism; the monumental triptychs of the 1970s seemed to derive their power from their abstract qualities: in the great black triptych recording George Dyer’s death alone in his hotel room, this document about pain ‑ the protagonist’s pain, the artist’s pain ‑ what mattered most was the density and incisiveness of the black and maroon quadrilateral shapes.

Where the constructed setting in Paris provided a relatively neutral modernist framework for the paintings, the grandiose neo‑classical spaces at Munich were as much a theatre as a set of galleries. You saw a picture in another room through a portal on which it was centred and it looked like a Velázquez hanging in the Prado.

Bacon’ s choice of pictures from the National Gallery’s collection for his exhibition in 1985 in the series called The Artist’s Eyeshowed a strong bias towards serene and monumental works such as Masaccio’s Virgin and Child and Seurat’s Baignade. He did have a still life and a landscape by van Gogh, but there was no figure‑painting that was at all expressionistic or even vigorously dramatic: Rubens’ Brazen Serpent had been on the list of possibles but was eliminated. Another artist left out in the end ‑ in this case one who would have fitted in was Raphael. He was left out because there was no particular example that Bacon loved enough, but, had the NG’s collection included the tapestry cartoons, which he often went to see at the Victoria & Albert Museum, I feel sure that The Miraculous Draught of Fishes would have been in the exhibition.

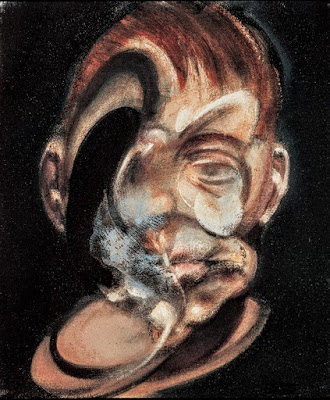

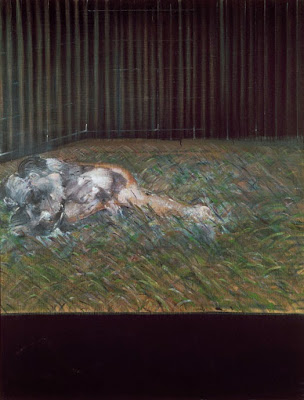

Something in the hang came as a revelation to me. In the middle of the best wall Bacon placed three great nudes: Degas’ pastel, Woman Drying Herself in the centre, flanked by Velázquez’ Rokeby Venus and the Michelangelo Entombment. Degas was the marriage of Velázquez and Michelangelo and thus Bacon’s key painter. It was a revelation because of the way it made an unwitting art historical point, not because there had ever been any doubt about how crucially those three artists had influenced Bacon. For example, in his earliest surviving image of a nude, Study from the Human Body, 1949, the treatment of the spine clearly reflects his fascination with how the top of the spine in Woman Drying Herself ‘almost comes out of the skin altogether’, as he put it, making us ‘more conscious of the vulnerability of the rest of the body’. In other respects this particular Bacon nude is less like a Degas than many others in that the realisation is more smudgy and atmospheric and evanescent, less incisive, than in later works. It is wonderfully tender and mysterious in its rendering of the space between the legs and its modelling of the underside of the right thigh. Its use of grisaille is breathtaking. None of Bacon’s paintings puts the question more teasingly as to whether he is primarily a painterly painter or an image‑maker. Does this work take us by the throat chiefly because of its lyrical beauty or because of the elegiac poignancy of its sense of farewell?

David Sylvester, The Supreme Pontiff, 1998 (New York, Tony Shafrazi Gallery, Francis Bacon: Important Paintings from The Estate, 1998). Francis Bacon’s first painting of a pope was Head VI of 1949, a head‑and‑shoulders image which already presented the inspired conflation between the Velázquez portrait of Pope Innocent X and the close‑up of the nanny shrieking from Eisenstein’s Battleship Potemkin. While that conflation was often repeated, not all Bacon’s popes have open mouths, nor are these necessarily shrieking. There are times when the open mouth looks as if it is silent, is the mouth of an asthmatic trying to take in air or that of an animal in a threatening or defiant pose.

Furthermore, not all Bacon’s popes are based on the portrait of Innocent X, though most of them are. He had a tremendous drive to make variation after variation on this image. Velázquez was his preferred painter and this particular portrait could have been expected to have an especial appeal to him in that the paint is freer and looser and the whites more flickering than in any other Velázquez, almost as in a Gainsborough. But Bacon never in fact saw the work in the original, not even when he spent some weeks in Rome in 1954; he knew it only in reproduction, and reproductions convey no hint of its freedom of handling.

Was Bacon, then, drawn to this particular Velázquez by its subject? The Pope is Papa and Bacon had very strong feelings about his father. “I disliked him, but I was sexually attracted to him when I was young. When I first sensed it, I hardly knew it was sexual. It was only later, through the grooms and the people in the stables I had affairs with, that I realized that it was a sexual thing towards my father.” Painting popes in their isolation could well have been, among other things, a way of bringing back his father, of spying on him, of demolishing him. Bacon believed or said merely that the Velázquez Pope was “one of the greatest portraits that have ever been made” and that he was obsessed by it because of “the magnificent color of it.” But in the forties and fifties he toned down the magnificent scarlet to a muted purple. It was not until the sixties that he was able to bring himself to match the scarlet.

Of all the innumerable popes, the greatest, it seems to me, were painted at the beginning ‑ Head VI and then the earliest of the versions in which the Pope is shown seated, Study after Velázquez, 1950. Behind the Pontiff is a heavy curtain with deep parallel folds; a second curtain, attached to a curved rail, is spread out across the foreground. This curtain, of course, alters the composition radically. The Velázquez is a seated three-quarter length portrait, cut off at the knees, and therefore still a medium close‑up. This Bacon Pope is cut off just above the knees, but then the foreground curtaining intervenes and, animated by the thrust of its radiating folds, pushes us back and creates a gap like an orchestra pit between audience and scene. We are made to keep our distance.

The figure is at once monumental and evanescent. Its majestic composure is frayed at the edges by a flicker that could mean both an emanation of its own nervous energy and a bombardment by pressures in the atmosphere. The mouth is immense in power and anguish. As we zoom in, it threatens to engulf us, to swallow us up. This is a mouth that is breathing in, or trying to. It is uttering no sort of cry. It is open and silent.

Magnificent and vulnerable, this personage has the withdrawn look of many Velázquez portraits, for instance, of the late head‑and‑shoulders of Philip IV in the National Gallery, London ‑ and not only the withdrawn look but the elongated Bourbon features. Velázquez is also there in the beautiful dryness of the paint. For me, this picture’s closest rival among the three‑quarter‑length popes is the gorgeous version done in 1953 which belongs to Des Moines, one of those Bacons that is peculiarly evocative of Titian, a painter in whom Bacon was not greatly interested. When we were talking about Titian once, he said: “When I think of the Pope painted by Velázquez, of course he wanted to make it as much like a Titian as he could, but in a curious way he cooled Titian.” It was this cooling that made Bacon love Velázquez as he did.

Hugh M. Davies, Bacon's Popes: Ex Cathedra to in Camera, 1999 (San Diego, Museum of Contemporary Art, Francis Bacon: The Papal Portraits of 1953, 1999). Throughout his long career, Francis Bacon (1909‑1992) steadfastly focused on the human figure as the subject of his paintings. Unlike other major artists of his time who reveled in abstraction, such as Jackson Pollock and Barnett Newman, Bacon never deviated from his commitment to making images of people. Yet while extending the timeless tradition of figuration, he invented profound and startling new ways of portraying people as he distorted the inhabitants of his painterly world in order to “unlock the valves of feeling and therefore return the onlooker to life more violently.”

Bacon’s most recognizable image, and hence most famous painting, is the screaming pope of Study after Velazquez ‘s Portrait of Pope Innocent X of 1953. The picture was inspired by Diego Velázquez’s extraordinarily lifelike portrait of a powerful and unscrupulous pope who duplicitously took the name Innocent. Painted in i6o at the height of the Baroque period, shortly after his arrival in Rome from Spain, it was Velázquez’s eminently successful attempt to rival the portraiture of Titian and the great painters of Italy. The subject of the painting is arguably the most powerful man in the world. He sits confidently on the papal throne, fully at ease ex cathedra‑literally, from the cathedral seat‑as God’s representative on earth.

The true brilliance of Velazquez’s accomplishment in this painting is to have satisfied his demanding papal client with a flattering, beautifully rendered portrait while at the same time passing on for the ages the unmistakable hint of corrupt character and deep‑seated deceit behind that well‑ordered and stern façade.

“Haunted and obsessed by the image … by its perfection, 112 Bacon sought to reinvent Velázquez’s Portrait of Pope Innocent X in the papal portraits that form the focus of this book. In the great painting from the Des Moines Art Center, the Study after Velazquez’s Portrait of Pope Innocent X, Bacon updates the seventeenth‑century image by transforming the Spanish artist’s confident client and relaxed leader into a screaming victim. Trapped as if manacled to an electric chair, the ludicrously drag‑attired subject is jolted into involuntary motion by external forces or internal psychoses. The eternal quiet of Velázquez’s Innocent is replaced by the involuntary cry of Bacon’s anonymous, unwitting, tortured occupant of the hot seat. One could hardly conceive of a more devastating depiction of postwar, existential angst or a more convincing denial of faith in the era that exemplified Nietzsche’s declaration that God is dead.

In Bacon’s words: “Great art is always a way of concentrating, reinventing what is called fact, what we know of our existence‑a reconcentration… tearing away the veils that fact acquires through time. Ideas always acquire appearance veils, the attitudes people acquire of their time and earlier time. Really good artists tear down those veils.”’

In much the same spirit that Velázquez went to Rome, determined to vie with the state portraits of Titian and remake them in the image of his time, Bacon’s papal variations are his attempt to reinvent or reinterpret Velázquez’s image in a way that would be valid for the mid‑twentieth century. To accomplish this reinvention, Bacon essentially replaced the grand, official state portrait with an intimate, spontaneous, candid camera glimpse behind the well‑ordered exterior. While Velázquez portrayed the pope ex cathedra, Bacon might be said to have captured him in camera‑as if behind a closed door or through a one‑way mirror. While Innocent directly confronts his audience with a confident, almost contemptuous gaze, Bacon’s pope, preoccupied by pain, seems oblivious to observation.

Richard Calvocoressi, Bacon: Public and Private, 2005 (Edinburgh, National Galleries of Scotland, Francis Bacon, Portraits and Heads, 2005). Now that Francis Bacon (1909-1992) has been dead for over a decade, and we can begin to form some sort of perspective on the twentieth century, the scale and significance of his achievement are becoming increasingly apparent. With the exception of Picasso and Andy Warhol, both of whom have museums dedicated to their life and work, we probably know more about Bacon than any other modern artist. This is ironic given how extensively Bacon edited his artistic past. But the gift, in 1998, of his London studio and its contents to the city of Dublin and its faithful reconstruction in the Hugh Lane Gallery, have transformed Bacon studies. Some 7,500 items were discovered in the studio, where the artist lived and worked for over thirty years, and the gallery has catalogued and entered every single one onto a special database. These entries give a unique insight into Bacon’s eclectic sources, preoccupations and working methods.

A handful of exhibitions has been staged in the last three or four years exemplifying this new, analytical approach to Bacon’s art, culminating in the magisterial Francis Bacon and the Tradition of Art (Vienna and Basel, 2003-4). This examined the full range of Bacon’s work in the context of those artists from European high culture whom he appropriated and assimilated Michelangelo, Velázquez, Rembrandt, Ingres, Degas, Van Gogh, Picasso as well as the motifs and subjects that obsessed him: papal imagery; curtains and veils; the open mouth; the cage; circular forms, spaces and structures; the male human body; portraiture; mirrors and reflections; the shadow; the Crucifixion; meat and flesh. More recently, Martin Harrison in his book In Camera has revealed the extent to which Bacon based many of his most memorable images on ‘low art’ sources such as photographs and film stills torn from books, magazines and newspapers. In his interviews with David Sylvester from the early 1960s onwards, Bacon readily admitted his debt to the great art of the past, which he knew only in reproduction, and often referred to his use of Eadweard Muybridge’s sequential photographs of human figures and animals in action. But Harrison draws attention to a stratum of less elevated imagery which fascinated Bacon and which his friend the painter and photographer Peter Rose Pulham called ‘bad Press photographs reproduced through a coarse screen on bad paper’.’ Harrison also convincingly points to an obscure German book on spiritualism, with trick photographs of ectoplasms, emanations and other psychic phenomena, as an important source which the artist did not acknowledge; a paint spattered and well thumbed copy was found in Bacon’s studio.

Bacon liked the news photograph because it was instantaneous and to a large degree reliant on chance. In its fluidity and suppression of detail, it suggested transmutation and flux qualities he tried to capture in his own radical manipulation of paint. David Sylvester, in a lecture on the artist (given in 2001 but not published until this year), argues that the main reason Bacon worked from the photographic image rather than from life was that ‘it is easier to make a flat image … based on the observation of an existing flat image than it is to make a flat image based on the observation of something in the round’. In other words, Bacon, who lacked the traditional artschool training of painting or drawing from a living model, found that photographs had already done some of the work of translating threedimensional form into twodimensional form for him. Bacon painted a small number of portraits from life in the 1950s but from the early 1960s preferred to work from commissioned photographs of friends and lovers which functioned as a kind of aidememoire while he tried to imagine their presence on canvas. Their actual presence in the studio, he claimed, would have inhibited his freedom to ‘distort’.

Until recently, Sylvester’s series of conversations with the artist, first published in 1975 and twice expanded in the 1980s, was one of the most quoted texts on any twentieth century artist. Interviews with Francis Bacon helped make Bacon a public figure, or at least a very public kind of artist, in his lifetime. Shortly before his death in 2001, Sylvester published Looking back at Francis Bacon, a collection of essays, thoughts and new biographical material to which he added previously unpublished extracts from his recorded interviews with the artist. In one section, ‘Bacon’s secret vice’, Sylvester was forced to correct the impression, which Bacon himself had been careful to promote in their conversations, that the artist never made preliminary studies before starting a painting; over seventy rapid, perfunctory sketches were found in Bacon’s studio before it was transported to Dublin. Bacon also made lists of ideas for paintings on scraps of paper and on the inside covers of books. But both categories should be seen as substitutes for fully workedout compositional studies in the same way that photographs were including photographic reproductions of his own work, which Bacon increasingly ‘quoted’ as he got older. So, in spite of such minor ‘economies with the truth’, Interviews with Francis Bacon will remain an essential resource for many years to come, especially when read in conjunction with Sylvester’s final revisions and reflections on this most profound and complex of painters.

There is another, more obvious sense in which Bacon was a public artist. From 1962 until his death thirty years later, he released into the world, at the rate of almost one a year, twenty eight large triptychs: that is to say, canvases each nearly two metres high by one and a half metres wide, grouped in threes eightyfour panels in total. Each panel usually contains a centrally placed figure, or a pair of coupled figures, alive with painterly incident, set off against broad, flat expanses of thinly applied colour that appear to parody abstract painting. Although presented serially, the narrative link between each panel is not always clear, if indeed it exists. A number of these triptychs hang in prominent museums around the world, where they are difficult to ignore: like the medieval or Renaissance altarpiece from which their format derives, they imply portentous, if highly ambiguous, public statements. Many of them address archetypal subjects, such as violent death, sexual ecstasy (and their interconnection), mutability and loss, and invoke earlier treatments of these themes in classical Greek tragedy, Christian iconography and the poetry of T.S. Eliot. A few incorporate images of contemporary political figures or events. Even when they have a commemorative purpose, as in those recalling Bacon’s deceased lover George Dyer, there is something theatrical about them, reinforced by the spaces in which their dramas are enacted, like stages or arenas, which presuppose an audience. As Sylvester commented, ‘Bacon had something of Picasso’s genius for transforming his autobiography into images with a mythic allure and weight’.

Martin Harrison, Studying Form, 2005 (London, Faggionato Fine Art, Francis Bacon Studying Form, 2005). Since David Sylvester was too unwell to deliver Francis Bacon and The Nude in person, he wrote down the lecture and tape‑recorded it: the transcript is published here for the first time. I was unable to attend the transmission of David’s talk in Dublin, and did not see the text until after my book, In Camera: Francis Bacon was on press. Had I done so, I would either have modified, or expanded, my readings of three decisive Bacon paintings. I saw David fairly frequently towards the end of his life, and although we talked at length about everything from Flemish tapestry to Barnett Newman, to my regret we seldom spoke about Bacon. In the hope that it may inform both my own text and David’s, I shall begin this essay by instigating an unrealised dialogue.

In his analysis of Study from the Human Body, 1949, Bacon’s first (extant) painting of the nude, Sylvester remarked on the significance of the example of the pastels of Degas for the striated treatment of the curtain the “shuttering” as Bacon termed it. He cited an interview he had conducted in which Bacon explained that by using shuttering, “the sensation doesn’t come straight out at you but slides slowly and gently through the gaps”: this was a lucid description of a technique of optical disturbance, one of Bacon’s tactics for obstructing narrative and destabilizing and fragmenting his figures, and a strategy that is partly in conflict with his professed aim to achieve the ‘brutality of fact’. Almost as an aside, Sylvester mentioned the conviction of Bacon’s cousin, Pamela Firth, that in Study from the Human Body the figure’s truncated arm referred to her husband, Lt Col Vladimir Peniakoff (of Popski’s Private Army renown), who had lost his left hand in battle. While this is perfectly plausible, I would propose another, and perhaps in Bacon’s thinking prior, quote (consistent with Bacon’s synthesizing of multiple quotations): the figures at the left and right sides of Matisse’s Bathers by a River, 1909‑16. Sylvester believed that the same Matisse had informed Bacon’s Painting 1950, a painting for which I proposed a wider range of ‘sources’, including a different Matisse: on this point we may both be right.

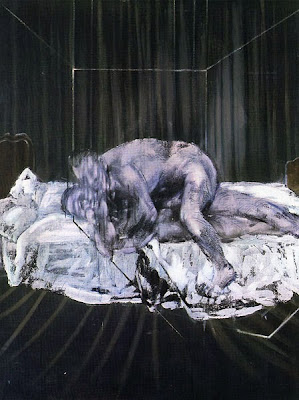

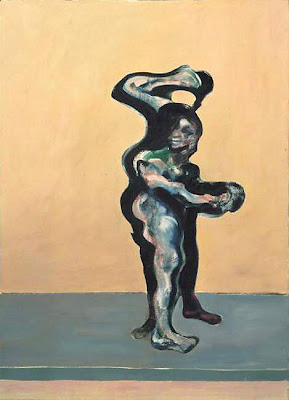

Regarding Triptych–Studies of the Human Body, 1970, Sylvester confessed his theory that the source for the figure in the right‑hand panel was Caravaggio’s Narcissus, was “pure supposition”; however, having absorbed the remarks on this painting in Looking Back at Francis Bacon, my subsequent comparison of the figure’s prominent right shoulder with Caravaggio’s St John the Baptist appears to strengthen the fink.’ Francis Bacon and the Nude proved to be Sylvester’s final contribution to Bacon studies. In the course of it he also discussed one of the paintings in the present exhibition, Lying Figure, No 2, 1959, which he related, convincingly, to the two Tate gouaches; indeed he linked the gouaches to all of the paintings of lying and reclining figures that Bacon painted between 1959 and 1961. Since he also believed that, for these figures, “no prototype in art or photography has been traced”, presumably he was convinced neither by the arguments for the sculpture of Rodin nor the fragmented statues of antiquity as significant precedents for their extravagantly and unconventionally splayed limbs.’

Victoria Walsh, Real Imagination is Technical Imagination, 2008 (London, Tate Britain, Francis Bacon, 2008). Like Oscar Wilde, with whom he shared a love of literature, theatre and creative artifice, Bacon was acutely conscious of the value of constructing a public image and perfectly adept at carefully orchestrating both it and the reception of his work from an early stage. Marking out his serious pedigree in 1950, he identified himself in the catalogue to the exhibition London-Paris: New Trends in Painting and Sculpture as “the collateral descendant of the Elizabethan philosopher”; he latter admitted in an interview in 1973 that he had no firm evidence for this, although he shared a homosexual disposition with his purported eponymous ancestor. In interviews, Bacon held tight control of the final published texts and indeed, while they have attained a canonical status in Bacon studies, the published interviews with David Sylvester only represent a fifth of the original exchanges between the two. In the Preface to the interviews, Sylvester acknowledged, in what almost reads as an apology or disclaimer, just how radical their reformatting and editing had been:

“since the editing has been designed to present Bacon’s thought clearly and economically…the sequence in which things were said has been drastically rearranged. Each of the interviews, apart from the first has been constructed from transcripts of two or more sessions, and paragraphs in these montages sometimes combines things said on two or three different days quite widely separated in time. In order to prevent the montage from looking like a montage, many of the questions have been recast or simply fabricated. The aim has been to seam together a more concise and coherent argument than ever came about when we were talking.”

Whether it was Bacon’s concern to maintain the accumulative aura of his work or his disdain of potentially reductive interpretations, his desire to frustrate an empirical analysis of his oeuvre was highlighted in a now legendary anecdote: on a visit to the artist, a researcher enquired of Bacon whether he intended to bequeath his archive at the end of his life, to which Bacon promptly responded by sweeping up everything in sight, placing it in plastic bags and creating a bonfire of all the contents. As Martin Harrison also noted, Bacon “effectively censured…the iconological study of his paintings, initially by denying their iconographies. Most critics acquiesced in this denial of content, and those who transgressed risked his non co-operation regarding reproductions rights: this enforced collaboration in this information clamp-down helped to censure that Bacon’s paintings, and his procedures were investigated and understood largely on the terms he dictated, or of which he approved.”

Manuela Mena, Bacon and the Spanish painting: « The way to dusty death », 2009 (Madrid, Museo Nacional del Prado, Francis Bacon, 2009). Francis Bacon died in Madrid on April 28, 1992 and was incinerated the following day in the prosaic cemetery of La Almudena without any witness or ceremony. « The way to dusty death » brought him to the same city where Velázquez died. Surely, he would have liked this coincidence, which seemed like a voluntary homage to the Spanish painter or was it intentional? MacBeth impressed him with “his famous lines about death and the shortness of life, about the passing of time and then nothing makes any sense at all” and this also reflected his own vision of man: he is nothing but an accident of life, a “completely futile being that has to play out the game without reason”.

The concept of Shakespeare on the shortness and vanity of life and the inexorability of death also imbued with the Spanish culture of the 18th century at the time of Velázquez.

Therefore, as Bacon admitted, there were still “a certain type of religious possibilities” to which man could hold on to but now in the 20th century, “has had completely cancelled out for him”. The same idea had been expressed by a contemporary of Bacon: Dietrich Bonhoeffer, the German theologian whose writings Bacon most certainly knew: “We are moving towards a completely religionless time; people as they are now simply cannot be religious any more”. With everything, Bacon wanted to fill the futile and gratuitous journey towards death with ”certain grandeur” –in his case with his art. He always considered life, this journey between birth and death, like “an unbearable idea” and endeavoured to throw himself into an activity, which would give “a sense to this pointless existence.”

The State of Francis Bacon