Francis Bacon, British painter, self-taught artist, 1909-1992

Mariano Akerman

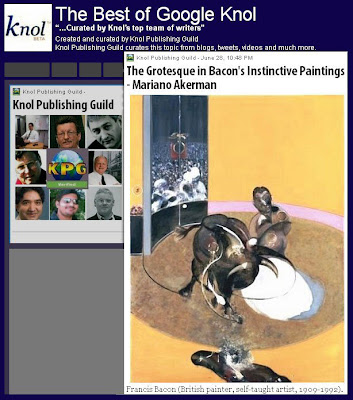

The Grotesque in Francis Bacon's Instinctive Paintings

1999

Artistic Grotesqueness

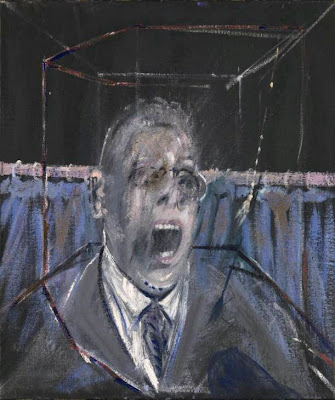

A critic in a British newspaper, 1985: One day he amused me by saying, in an apologetic tone: "You know, I think I've got the scream, but I am having terrible trouble with the smile." The truth was that he could get no kicks from an image of a smiling face.

"

Perhaps one day I will manage to capture an instant in all its violence and all its beauty" (Bacon).[1]

|

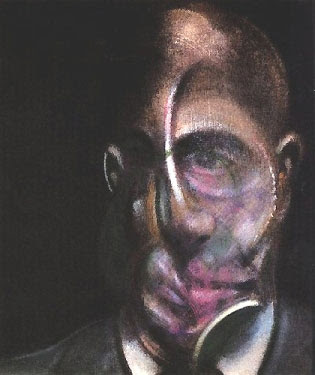

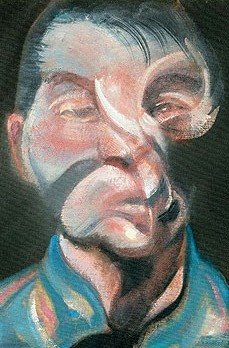

1. Francis Bacon, Portrait of Michel Leiris, 1976

Oil on canvas, 35.5 x 30.5 cm.

Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris |

Francis Bacon's paintings are mysterious and suggestive. They are ambiguous and constitute symbols of multi-leveled significance, which is conveyed through the artist's manipulation of the grotesque.

|

2. Bacon, Lying Figure in a Mirror, 1971

Oil on canvas, 198 x 147.5 cm.

Museo de Bellas Artes, Bilbao.[2] |

As configurations of the ambiguous, Bacon's pictures engender both curiosity and perplexity. They often produce mixed feelings, such as attraction and repulsion at the same time. For a well-balanced yet disquieting interplay between fear and desire, vulnerability and cruelty, suffering and apathy is characteristic of Bacon's instinctive paintings.

|

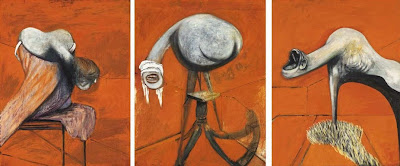

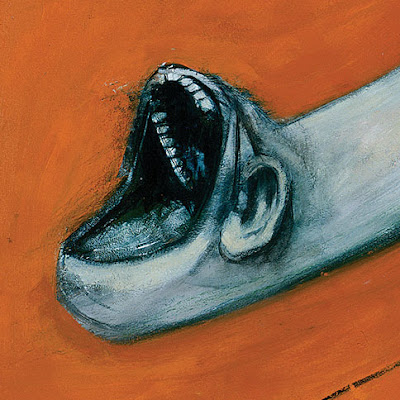

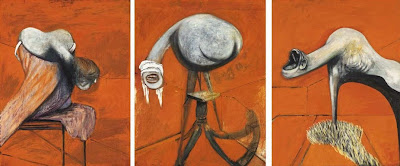

3. Bacon, Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion, 1944

Oil on board, each panel 95 x 73.5 cm. Tate Gallery, London.[3] |

Tension and intensity, the combination of incompatible elements, and suggestions of the monstrous or the inhuman abound in the artist's imagery.

|

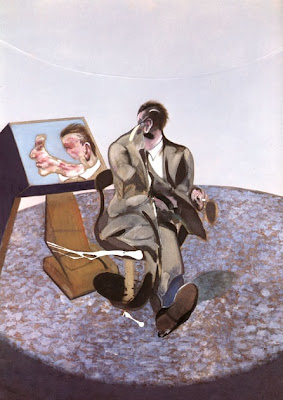

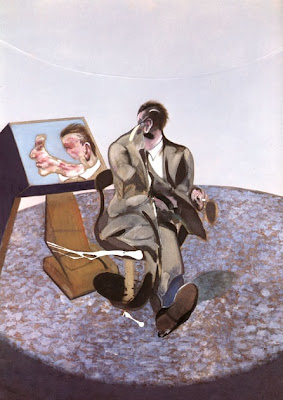

4. Bacon, Portrait of George Dyer in a Mirror, 1968

Oil on canvas, 198 x 147.5 cm

Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid.[4] |

Bacon uses the grotesque as a means of self-expression enabling him to ambiguously communicate not only his fascination with power and violence, but also his haunted condition. The grotesque thus becomes a means of simultaneous purgation and transcendence.

|

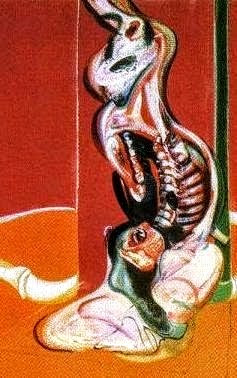

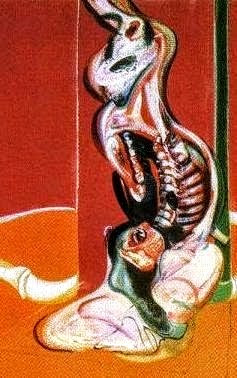

5. Bacon, Motif from the right-hand panel of Three Studies for a Crucifixion

1962. Oil on canvas. The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York.[5] |

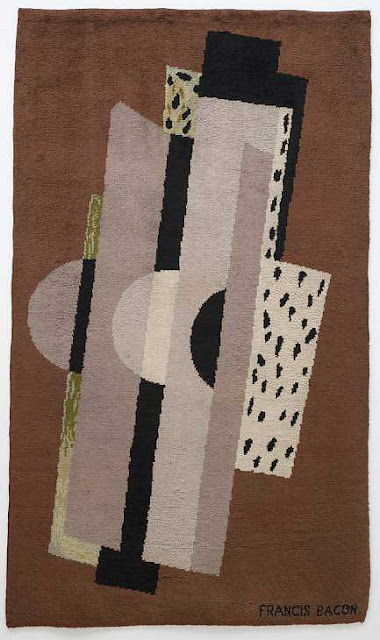

Aside from their extravagance, Bacon's instinctive paintings are far from being

ornamental accesories (eg., Italian

grotteschi and other European designs in

auricular style such as Dutch

Kwabornament and German

Knorpelwerk). In fact, the instintive paintings are inalienable personal reports encapsulating a private truth: the artist's contradictory feelings and sensations, which are neither decorative nor entirely evasive.

|

6. Bacon, Fragment of a Crucifixion, 1950

Oil and cotton on canvas, 139 x 108 cm.

Stedelijk van Abbenmuseum, Eindhoven.[6] |

Through his instinctive paintings, Bacon willingly walks along the border of an emotional precipice, suggesting his obsession with sex and death, his apathy in matters of vulnerability and suffering, and his fascination with power and aggressiveness.

|

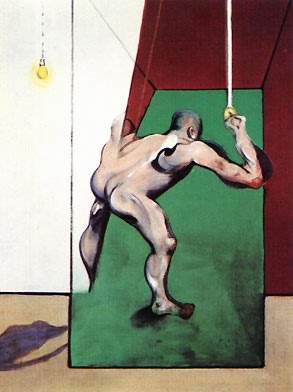

7. Bacon, Study from the Human Body, Figure turning on the Light, 1973-74

Oil on canvas, 198 x 147.5 cm.

Formerly in The Royal College of Arts, London.[7] |

The suggestiveness of Bacon's art at once reveals and conceals the artist's ultimate intentions in such a blurred way that identity itself becomes problematic in his imagery. By depicting the ambiguously combined and the equivocally suggestive Bacon disorients the viewer, who cannot establish a precise meaning in his ever-changing images. Various readings are thus possible and they seem all equally valid.

|

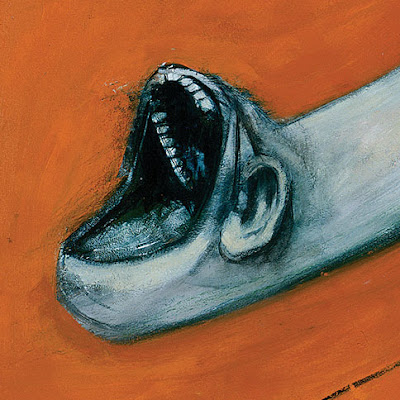

8. Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion

right-hand panel, close-up

Tate, London.[8] |

Considering that instinct implies the abolishment of morals, at the time of contemplating Bacon's paintings, we are to arrive at our own moral conclusions (certainly irrelevant to the artist and his calculated lack of concern). At this point, everything melts under our feet, because in Bacon's grotesque realm the only safe given is insecurity.

|

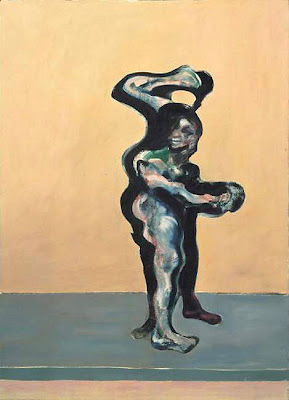

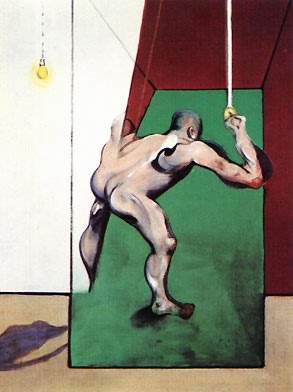

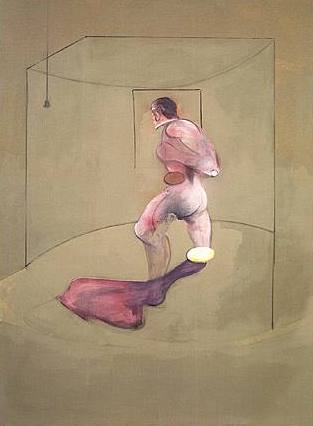

9. Bacon, Study of the Human Body, Figure in Movement, 1982

Oil on canvas, 198 x 147.5 cm.

Marlborough Fine Art, London.[9] |

Bacon’s instinctive art, on the other hand, is certainly not the product of accident or chance, as the artist liked to claim from the mid-1960s onwards. They constitute carefully planned compositions which are inextricably related to the artist's life and also function as mysterious, anti-illustrational traps that suggest the monstrously cruel.

|

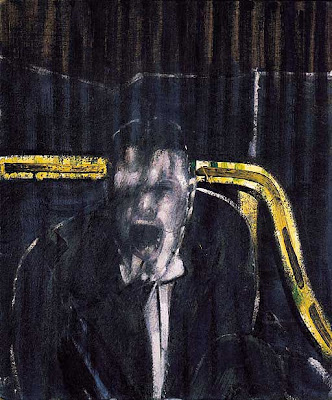

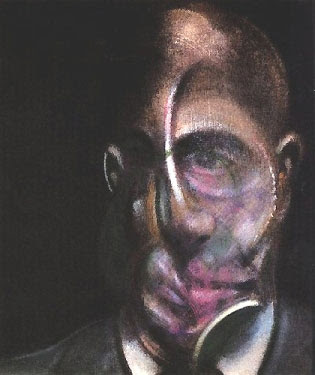

10. Bacon, face of Man in Blue VI, 1954

Oil on canvas, detail

Private collection.[10] |

In this context, we realize Bacon's manipulation of the grotesque and the artist's fundamental intervention in turning it into a useful vehicle for self-expression. Bacon's instinctive images are thus profound but also problematic—a New Grand Manner of Painting merging the defiantly powerful, the disquietingly extraordinary, the suggestively monstrous, the sarcastically allusive, the theatrically manipulative, and the extremely personal.

|

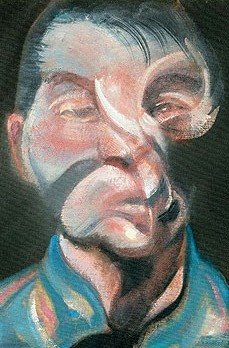

11. Bacon, Self-Portrait, 1972

Oil on canvas, 35.5 x 30.5 cm.

Gilbert de Bottom Collection, Switzerland |

As a species of confusion par excellence, the grotesque suspends belief and invites a search for meaning. Pushing us to consider alternative possibilities, the grotesque paralyses language and challenges categories. Grotesque art is thus thought-enlarging art.[11] This is true in Bacon's case, whose grotesque art conveys immediacy and suggests multilayered ideas granting us an active role as both spectators and interpreters. This is possibly the ultimate meaning of the artist's pictorial freedom, which he has achieved through a singular manipulation of the grotesque.

|

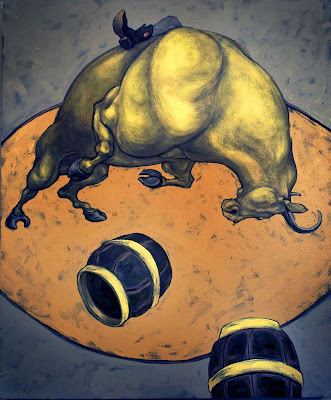

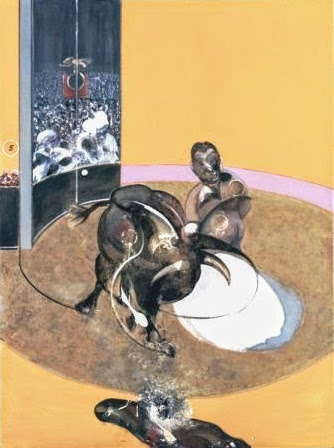

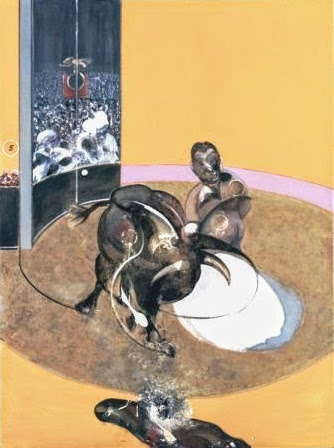

12. Bacon, Study for Bullfight No.2, 1969

Oil on canvas, 198 x 147.5 cm

Musée des Beaux-Arts, Lyon. [12] |

The ambiguous element that inhabits Bacon's instinctive paintings has an immense capacity to open the valves of feeling. It is this expressive, ever-changing element of Bacon's suggestive art which proves to be extraordinarily rich: pictorial freedom is a provocative, grotesque element which coherently unites Bacon's truth and our freedom.

|

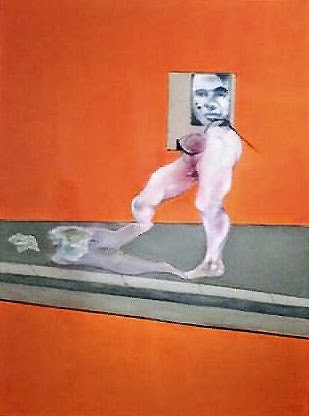

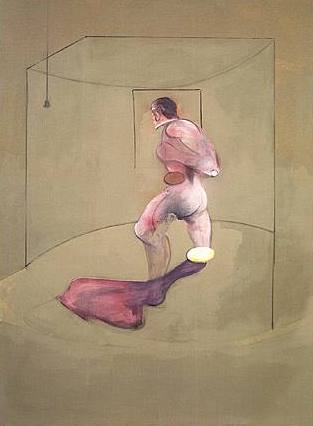

13. Bacon, Study from the Human Body after Muybridge, 1988

Oil on canvas 198.1 x 147.3 cm

Tony Shafrazi Gallery, New York.[12] |

Notes

"The Grotesque in Bacon's Instinctive Paintings" is based on Mariano Akerman, The Grotesque in Francis Bacon's Paintings, M.A. thesis, July 1999 © 1999-2009, by the author.

1. Bacon, quoted by Paloma Alarcó, 2001 (

Retrato de George Dyer en un espejo,

Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid; 19.2.2009).

2. Mariano Akerman,

Figura en el espejo,

Plenitud, 4.3.2008

3. "When this triptych was first exhibited at the end of the war in 1945, it secured Bacon’s reputation. The title relates these horrific beasts to the saints traditionally portrayed at the foot of the cross in religious painting. Bacon even suggested he had intended to paint a larger crucifixion beneath which these would appear. He later related these figures to the Eumenides – the vengeful furies of Greek myth, associating them within a broader mythological tradition. Typically, Bacon drew on a range of sources for these figures, including a photograph purporting to show the materialisation of ectoplasm and the work of Pablo Picasso" (

Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion, Tate Gallery, London, exhibition label, May 2007). See also

Wikipedia.

4. "En este doble retrato, George Dyer, el amante de Bacon durante años, está sentado en una silla giratoria frente a un espejo colocado sobre un extraño mueble con peana. La violencia y brutalidad de la imagen, con el cuerpo distorsionado y la cara retorcida por un espasmo, está agudizada por un halo de luz circular que proviene de un foco situado fuera del cuadro. En contraposición, la cara reflejada en el espejo, escindida en dos por una franja de espacio luminoso, no sufre las mismas distorsiones. Si pudiéramos unir las dos mitades, tendríamos un retrato bastante naturalista del modelo, con su perfil anguloso de nariz ganchuda y una expresión que combina deseo y muerte. Bacon, en la estela de los retratos dislocados de Picasso de los años centrales del siglo pasado, logra traducir los aspectos más sórdidos del ser humano" (

Retrato de George Dyer en un espejo, Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza; 30.10.2009). "Ejemplo de la capacidad de Bacon para acercarse al interior de la mente de sus retratados, la anamorfosis en el espejo sirvió en esta obra para confrontar al modelo con su retrato y su reflejo, al tiempo que no deja su papel como recuerdo aterrador de la amenaza del tiempo y de la muerte. El espasmo retorcido del rostro de Dyer se contrapone a la cara reflejada en el espejo, escindida en dos por una franja de espacio luminoso que parece un reflejo en el cristal. Al igual que todos los personajes de Bacon, George Dyer está representado en solitario, aislado en un espacio vacío, para simbolizar la soledad del hombre en un mundo hostil y demostrando el clima existencialista de la Europa de entreguerras en el que se formó" (

EducaThyssen, 31.10.2009).

5. "In 1944, one of the most devastating years of World War II, Francis Bacon painted Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion. With this horrific triptych depicting vaguely anthropomorphic creatures writhing in anguish, Bacon established his reputation as one of England’s foremost figurative painters and a ruthless chronicler of the human condition. During the ensuing years, certain disturbing subjects recurred in Bacon’s oeuvre: disembodied, almost faceless portraits; mangled bodies resembling animal carcasses; images of screaming figures; and idiosyncratic versions of the Crucifixion. One of the most frequently represented subjects in Western art, the Crucifixion has come to symbolize far more than the historical and religious event itself. Rendered in modern times by [many] artists [...], this theme bespeaks human suffering on a universal scale while also addressing individual pain. The Crucifixion appeared in Bacon’s work as early as 1933. Even though he was an avowedly irreligious man, Bacon viewed the Crucifixion as a “magnificent armature” from which to suspend “all types of feeling and sensation.” It provided the artist with a predetermined format on which to inscribe his own interpretive renderings, allowing him to evade narrative content—he disdained painting as illustration—and to concentrate, instead, on emotional and perceptual evocation. His persistent use of the triptych format (also traditionally associated with religious painting) furthered the narrative disjunction in the works through the physical separation of the elements that comprise them. / That Bacon saw a connection between the brutality of slaughterhouses and the Crucifixion is particularly evident in the Guggenheim’s painting. The crucified figure slithering down the cross in the right panel, a form derived from the sinuous body of Christ in Cimabue’s renowned 13th-century Crucifixion, is splayed open like the butchered carcass of an animal. Slabs of meat in the left panel corroborate this reading. Bacon believed that animals in slaughterhouses suspect their ultimate fate. Seeing a parallel current in the human experience—as symbolized by the Crucifixion in that it represents the inevitability of death—he has explained, “we are meat, we are potential carcasses.” The bulbous, bloodied man lying on the divan in the center further expresses this notion by embodying human mortality." Nancy Spector,

Three Studies for a Crucifixion, Guggenheim Museum, New York (30.10.2009).

6. "Magie rond de ‘Salonfähige uitbater van het erge’ is de titel die gekozen werd bij Fragment of a Crucifixion uit 1950 van Francis Bacon. Bacon schildert vrijwel altijd gekwelde personen en uit hiermee zijn gevoelens ten aanzien van het leven. Als persoon houdt hij graag controle. In de loop van zijn carrière creëert hij als een toneelspeler een sfeer rondom zichzelf en zijn werk waarbij het als buitenstaander moeilijk te zien is waar fictie ophoudt en werkelijkheid begint. Niet zelden wordt de indruk gewekt dat Bacon als het ware zijn schilderijen leefde." (Eindhoven, Van Abbenmuseum,

Mixed Messages, April-September 2008; trans.: Magic around the "socially acceptable operator of the worst" is the title that was chosen by Fragment of a Crucifixion in 1950 by Francis Bacon. Bacon paints almost always afflicted with this person and his feelings towards life. As a person he likes to keep control. In the course of his career as an actor, he creates an atmosphere around himself and his work in which the outsider is difficult to see where reality ends and fiction begins. Not infrequently the impression that Bacon, as it were his paintings survived; accessed 31.10.2009).

7. "To raise funds [...], Council agreed in June 2007 to the sale of a Francis Bacon painting Study from the Human Body, Man Turning on the Light, which was given by the artist as rent for a studio which he occupied in the College for a short period in the late 1960s. The painting was sold at Christie’s in October 2007 for just over £8m." (Christopher Frayling,

Accounts, Royal College of Art, London, 2006/7; PDF, 31.10.2009).

8. "The face of the figure is distorted into a scream of horrific intensity. He painted many screams in later works, but none can match the impact of this one. It is the scream of the torture victim at the very moment that the lash cuts the flesh. The victim, of course, is Bacon himself. He was heavily into bondage and masochistic ritual in his private life, and he relived his painful eroticism in many of his images of trussed up, agonised, distorted figures. / Francis was fascinated by extreme forms of facial expression, and the mouth stretched open to full gape was his favourite. One day he amused me by saying, in an apologetic tone: "You know, I think I've got the scream, but I am having terrible trouble with the smile." The truth was that he could get no kicks from an image of a smiling face. It was not part of his complex sexual obsession. / Others may see in this screaming face a reflection of the agonies of war-torn Europe, a statement about the horrors of modern existence, or the entrapment and isolation of modern man in his urban cell. I see nothing of the sort. I see a devout masochist enjoying the thrill of encapsulating the secret joys of his most private moments. The great mystery about Bacon's work is why this lifelong fetishistic indulgence should have resulted in the creation of such truly great art. But then mystery is the very essence of art. As Picasso once said: 'I don't understand it and if I did, I wouldn't tell you.' " (Desmond Morris,

On Francis Bacon's Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion,

Tate Etc., Issue 8, Autumn 2006, MicroTate; 31.10.2009).

9. "Francis Bacon (28 October 1909 – 28 April 1992) was a British figurative painter. He was a collateral descendant of the Elizabethan philosopher Francis Bacon. His artwork is known for its bold, austere, and often grotesque or nightmarish imagery. [...] Bacon came to London in 1925 and although he received no formal art training, he was a totally original artist whose work always contained a heroic grandeur. He created a sensation in 1945 when he exhibited his Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion at the Lefevre Gallery in London [...] now in the Tate Britain’s collection in London. [... Bacon had a predilection for the] triptych format and placing his work behind glass in heavily gilded frames; [also for] the open mouth and the use of painterly distortion. [...] Bacon’s work was Expressionist in style, albeit that his distorted human forms are unsettling. He developed his idiosyncratic style during the 1950s when he achieved an international reputation. In 1958 Bacon signed a contract with Marlborough who represented him exclusively worldwide until his death in 1992 (

Francis Bacon, Marlborough Fine Art, London; 31.10.2009).

10. "Man in Blue VI by Francis Bacon (estimate: £4,000,000 to £6,000,000) [...]. The finest of a series of seven major paintings that Bacon made in the spring of 1954, the present work dates to an intense [...] period in the artist’s career when he was in the midst of a tempestuous and violent romance with Peter Lacy, a veteran Spitfire pilot whom he described as the great love of his life. As Francis Bacon said of his relationship with Lacy, 'Being in love in that extreme way - being totally, physically obsessed by someone - is like having some dreadful disease. I wouldn't wish it on my worst enemy.' In 1954, as a result of the violent and divisive nature of their mutually destructive relationship, Bacon had moved out of the cottage that he shared with Lacy and was staying at the Imperial Hotel in nearby Henley-upon-Thames. It was during the 1950s that Bacon gained international recognition; his portraits and paintings of Popes were exhibited at museums around Europe and the United States. The seven paintings depicting Man in Blue are unusual in that Bacon appears to have painted the sitter from life, as opposed to using a photograph which was his usual method. The sitter is an unknown man who Bacon is thought to have met at the hotel in Henley. The work depicts an ordinary figure pulsating with life and apparent inner turmoil at the centre of a dark void. This form of depiction contrasts to that of the screaming agony of the heads and popes that the artist had been painting the previous year, and offers a more subtle representation of personal anxiety and torment" (Matthew Patton, "Francis Bacon's Man in Blue VI leads Christie's Auction of Post-War and Contemporary Art," Press Release, London, 14.1.2009;

PDF, 31.10.2009). See also Mariano Akerman,

Lo familiar vuelto inquietante,

Imaginarium, 13.3.2009

11. Geoffery Galt Harpham,

On the Grotesque: Strategies of Contradiction in Art and Literature, Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1982

12."Fasciné par la figure humaine depuis son entrée sur la scène artistique britannique avec le Triptyque de 1944, Bacon s'intéresse également au tableau "à sujet". En 1969, il peint trois études pour une corrida. Ce thème a pu lui être suggéré par son ami, l’écrivain Michel Leiris, auteur de livres sur la tauromachie ou encore par Picasso auquel il s’est si souvent référé dans son œuvre. Isolés dans un rond comme sur une piste, le torero et le taureau sont représentés affrontés dans l’arène. Le mouvement est suggéré par un jeu de courbes qui, sur le sol ou dans les airs, évoquent le tournoiement de la bête et les voltes de la muleta. Eliminant tout récit, Bacon donne une expression "strictement physique du jeu taurin" (Leiris). Si dans le tableau de Lyon, le grand aplat orange qui structure l’espace comporte encore un panneau ouvert où l’on aperçoit une foule, dans une autre version à la composition inversée, Bacon a fermé ce panneau. Traitées dans les mêmes tonalités de brun et de mauve, les deux figures sont indissociables l’une de l’autre. L’artiste a fait subir des déformations au corps du torero : en brossant et en nettoyant la toile, il a fait perdre à la tête sa forme humaine, lui donnant en retour des traits d’animalité. Le carré rouge qui domine la foule, frappé d’un cercle et surmonté d’une forme qui ressemble à un rapace, a été souvent rapproché d’un emblème nazi, issu de ces photographies d’actualité que Bacon collectionnait et qui jonchaient le sol de son atelier" (

Etude pour une corrida n° 2, Musée des Beaux-Arts, Lyon; 30.10.2009).

12. New York, Tony Shafrazi Gallery,

Francis Bacon: Paintings, April-May 2002. The exhibition was aimed "to bring to light the extraordinary relationship Francis Bacon had with John Edwards," with whom the painter "found a son and 'became' the loving father he had never had."

Excerpt from catalog (31.10.2009). Picture price at the Frieze Art Fair 2008: $9 Million (Scott Reyburn,

Frieze Week to Lure Billonaires with $9 Million Bacon Nude,

Bloomberg.com, 7.10.2009).

Images

Photographs and reproductions used for educational purposes exclusively. They all belong to their respective owners. Photo credits:

The Estate of Francis Bacon, 1.

Centre Pompidou, 2.

Museo de Bellas Artes de Bilbao, 3.

Tate Gallery, 4.

Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza, 5.

Guggenheim Museum, 6.

Van Abbemuseum, 7.

Royal College of Art, 8.

Tate Etc., 9.

Marlborough Fine Art, 11.

Plenitud, 12.

Musée des Beaux Arts de Lyon, 13.

Artnet.com

Resources

Painter Francis Bacon's Centennial Birthday

Tate Gallery

Idea, research and design: Mariano Akerman. Initial version: 30.10.2009 - Last version: 21.2.2011

© Mariano Akerman. All rights reserved. This article may not be reproduced or republished without the previous written consent of the author.