Julian Bell

Excerpt from The Cunning of Francis Bacon

The New York Review of Books

10.5.2007

Illustrations added by Mariano Akerman

Some 40 percent of a plate has been ripped out of the Atlas-Manuel des maladies de la bouche, a French translation of an 1894 German medical textbook. The torn-away trapezoid shows “Fig. 1”: a heavily retouched photo of lips prised apart by forceps to reveal gums disfigured by an abscess, chipped teeth, and froth about the tongue. The chromolithograph with its flesh reds stands as an oval vignette on the creamy fragment of coated paper. But then the scrap has been scuffed by brushes loaded with green and cerulean; there are fingerprints to the right in blue-black and mauve, little splats of yellow and scarlet. The paper’s edges are frayed and nicked, it has a riverine crack where those clutching fingers have bent it: a vertical sever being a further result of decades of overhandling.

Une maladie de la bouche

Lithograph by Anst F. Reichhold, Illustration of a mouth disease (syphilis), from a German medical manual, Munich, c. 1900, plate 9. Cf. F.E. Bilz, Syphilistische Ziekten, 1923

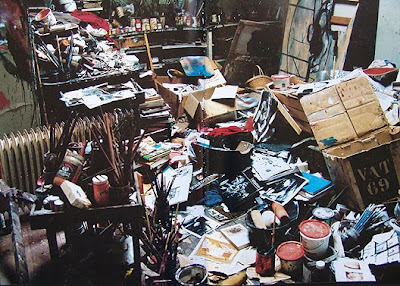

The item is among the several thousand catalogued in 1998 during the clearing of a smallish workroom in Reece Mews, Kensington, London SW7. This room was occupied by the artist Francis Bacon from 1961—when he turned fifty-two—till his death in 1992, thirty-one years later. For six years Bacon’s studio lay in an undisturbed limbo, but in 1998 negotiations between the Hugh Lane Gallery in Dublin, which houses one of Ireland’s leading collections of modern and contemporary art, and Bacon’s partner and heir John Edwards resulted in its entire contents (not only each scrap of paper, but even the paint-encrusted walls) being packaged and transported to the museum. There they were reassembled in a purpose-built display room, in exactly the disorder in which Bacon had left them in London. In this manner the painter (whose English father bred horses in Ireland) returned to the land of his childhood. The Hugh Lane’s curator, Margarita Cappock, reviews and analyzes the attendant inventory in her copiously illustrated volume, Francis Bacon’s Studio.

|

| Perry Odgen, 7 Reece Mews: Francis Bacon's Studio, photograph, 2001 |

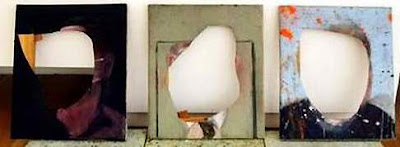

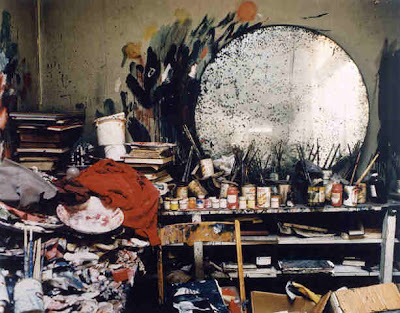

Mostly Cappock has papers to describe. Her team found printed pictures ripped not only from medical textbooks but from news magazines; trampled snapshots of Bacon’s friends; quick sketches for compositions; crumpled, scribbled agendas for imagery (“flesh-coloured shadows, “bed of crime,” “meat seen in a box”). There were weathered volumes of wildlife photography and art books reproducing Velázquez and Ingres. All these had been cast down among champagne cases, paint rollers, brushes, pots, and cans over the course of three decades, mounting up and moldering in ragged drifts around a walkway to the easel. On worktables, uncapped paint tubes had fused into mountainous conglomerates. By the walls and windows and also underfoot, a hundred slashed canvases lay strewn, with holes where faces once had been. Earlier photographic records indicate that a circular mirror with pocked silvering—a relic of the painter’s prehistory, his attempts while young to work in interior design—was one of the few items that had always stood proud of this dismal, dusty morass.

Francis Bacon on 7 Reece Mews: "I feel at home here in this chaos because chaos suggests images to me. And in any case I just love living in chaos."

|

| A slightly chaotic order |

|

| John Muybury recreated the images accumulated in Bacon's studio in a 1998 film entitled Love is the Devil; digital composition: Mariano Akerman. |

|

| Canvases slashed by the artist |

|

| The circular mirror |

Margarita Cappock, Francis Bacon's Studio, Merrell Publishers, 2005. Online description: "Francis Bacon (1909-1992) is regarded as one of the most important post-war painters, and his work is represented in major public collections worldwide. This is the first in-depth study of the rich contents of Bacon's studio in South Kensington, London, in which he worked from 1961 until his death. The studio contents totalled 7500 objects, including photographs, books and works on paper; together they offer unprecedented insights into the source materials and working methods of one of the giants of modern art."

D. Donovan, 2006: "His London studio, portrayed on the cover of FRANCIS BACON'S STUDIO, may look like a mess, but Francis Bacon was one of the most significant post-war painters and his studio, both home and workplace, was key to producing his art. His studio housed thousands of items central to his works and has been untouched since his death in 1992: it was donated in 1998 to the Dublin City Gallery and today curators have made it into a showpiece and work of art itself. The studio's deconstruction revealed over 7,500 objects from photos to illustrated publications, slashed canvases and his final unfinished work: FRANCIS BACON'S STUDIO provides the first in-depth survey of the studio and is essential for art library holdings and any student of Bacon's works."

Grady Harp, 2006: "Though there have been several excellent books written about the contents of Francis Bacon's 7 Reece Mews studio in London, the birthplace of his masterpiece paintings that still haunt the public and the historian minds, this hefty volume by Margarita Cappock offers more. Originally conceived as the book to document the 1998 move of Bacon's studio form Kensington, London to the Hugh Lane Gallery in Dublin where it remains an historic site, Cappock sorts and sifts through the bits of treasure and trash that influenced Bacon's inspiration for his future paintings.

Cappock betters the other books on this subject by illuminating the chards and tatters that most significantly influenced Bacon's thought development and because the book is so extensively illustrated, she is able to place side by side the instigating artifacts with the complete works. This book is by far the most intensive and exhaustive study of the influence of Bacon's studio and its detritus on the evolution of Bacon's paintings."

Other Available Resources

• Bacon's Work Document Ultimate Referent

• Bacon: Painter with a Double-Edged Sword

No comments:

Post a Comment