Pedro da Cruz,

Al borde del abismo,

El País, Montevideo, 18.9.2009

|

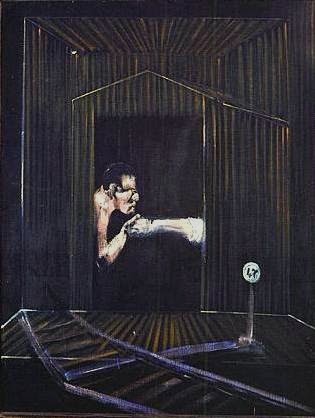

Francis Bacon

Fragmento de una crucifixión, 1950

Stedelijk van Abbenmuseum, Eindhoven |

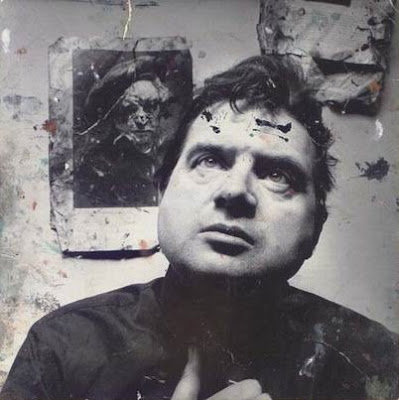

CONSIDERADO, junto a Lucian Freud, uno de los pintores ingleses más significativos del siglo XX, Francis Bacon continúa fascinando tanto al público como a la crítica. Su personalidad y su obra no cesan de ser discutidas y reinterpretadas, a pesar de que han transcurrido casi dos décadas desde que falleciera en Madrid en 1992. Debido a que el próximo 28 de octubre se cumplen cien años de su nacimiento, las actividades relacionadas con la obra de Bacon se han multiplicado.

En cuanto a las exposiciones conmemorativas, la más importante es la que recientemente reunió cerca de setenta de sus obras más conocidas. La muestra, una retrospectiva con obras fechadas entre 1933 y 1991, se inauguró en setiembre de 2008 en la Tate Britain de Londres, y fue luego exhibida en el Museo del Prado en Madrid y en el Metropolitan Museum de Nueva York. Con ocasión de la exposición fue publicado Francis Bacon, un voluminoso catálogo con excelentes reproducciones y textos de autores que discuten distintos aspectos de la obra del pintor.

Cabe preguntarse cuáles son las causas de la atracción ejercida por la obra de Bacon. Son innumerables telas -a pesar de que destruyó muchas de las primeras que pintó- producto de una larga y prolífica carrera de seis décadas. Las claves deben buscarse en la total unidad entre la vida del artista y su pintura. Una personalidad conflictiva, y una vida encarada como una continua toma de riesgos, siempre experimentados con intensidad: ya fueran una serie de "inconvenientes" relaciones homosexuales, las que nunca ocultó, o excesos con el alcohol y el juego (durante unos años prácticamente vivió en Montecarlo, donde jugaba a la ruleta).

Su obra plástica fue también resultado de continuos desafíos, de la búsqueda de caminos propios para expresar plásticamente su vida personal y su entorno, con las telas como un espacio de continua lucha creativa. En varias entrevistas Bacon expresó que su intención era "atacar el sistema nervioso del espectador, y reintegrar a éste a la vida con gran violencia". Para lograr ese objetivo deformaba las figuras, aunque tratando de conservar cierta relación con la realidad: "Lo que quiero es deformar el objeto hasta lo irreconocible, pero por medio de la deformación llevarlo de vuelta a ser un registro de su apariencia".

Según Bacon, su forma de trabajar era como "caminar continuamente al borde del abismo". El resultado plástico de esa sensación, que el pintor logra transmitir al espectador, es especialmente notable en sus autorretratos, así como en los retratos que pintó de amantes y amigos. El retrato se convierte en una construcción, cuyo verdadero motivo son las diferencias entre la apariencia física del modelo y su representación. Parafraseando al pintor, las figuras son mostradas como sistemas nerviosos expuestos y agredidos. Por lo que la contemplación de las obras puede ser una experiencia reveladora, pero también una vivencia revulsiva y dolorosa.

LOS COMIENZOS. Nacido de padres ingleses en Dublín, Bacon vivió allí, con excepción de los años en que la familia se trasladó a Londres a causa de la Primera Guerra Mundial, hasta el fin de la adolescencia. La vida del joven Bacon fue marcada por un continuo conflicto con su padre, un hombre de carácter intolerante y dictatorial. La situación se agravó cuando Bacon se negó a ocultar su orientación homosexual, y finalmente fue expulsado del hogar cuando su padre lo sorprendió probándose la ropa interior de la madre. A partir de entonces Bacon se liberó de las convenciones sociales y sexuales del entorno en el que había crecido, una actitud que mantendría durante toda su vida.

En la primavera de 1927 viajó a Francia, donde iba a permanecer hasta el fin del año siguiente. En París, en la Galería Paul Rosenberg, vio una exposición de Picasso que lo impactó profundamente. Allí también vio por primera vez el film de Sergei Eisenstein Acorazado Potemkin (1925), algunas de cuyas escenas le servirían de inspiración unos años más tarde. Luego de una corta estadía en Londres, Bacon volvió a viajar a Francia, y también visitó Alemania. De regreso en Londres probó distintos trabajos, entre otros el de decorador de interiores y diseñador de muebles, y el de valet, para el que ofrecía sus servicios bajo el nombre de Francis Lightfoot. Se instaló en una casa de South Kensington, que compartió con su antigua nanny (niñera), e inició su primera relación sentimental estable con el político conservador Eric Hall, lo que implicaba un riesgo, ya que las relaciones homosexuales entonces eran ilegales en Inglaterra (lo fueron hasta 1967).

En 1930 Bacon conoció al artista australiano Roy De Maestre, quien le enseñó a usar la pintura al óleo y lo introdujo en un círculo de coleccionistas, entre los que se contaba el influyente Douglas Cooper, y pintores como Graham Sutherland. Sin estudios formales, Bacon inició entonces su carrera de pintor. Fuertemente influido por la obra de corte surrealista que Picasso realizaba en esa época, pintó Crucifixión (1933), que fue incluida por el crítico Herbert Read en el libro Art Now del mismo año, lo que dio notoriedad a su obra.

En los años siguientes Bacon expuso regularmente, pero en 1944, hacia el fin de la Segunda Guerra Mundial, destruyó la mayoría de las obras que había pintado hasta entonces. A su vez, ese mismo año, pintó un extraordinario Tres estudios para figuras en la base de una crucifixión, tríptico con dramáticas figuras antropomórficas. Bacon había encontrado un motivo, la figura humana, que sería central en su obra hasta el final de su carrera. Pintaría al hombre en una situación de conflicto y violencia, figuras deformadas que, encerradas en un entorno abstraído, sufren y gritan su dolor.

Entre sus obras más conocidas de entonces se pueden nombrar Figura saliendo de un auto (1943), Figura en un paisaje (1945), Estudio de figura I (1946). También Pintura (1946), con un hombre bajo un paraguas entre dos medias reses, y una serie de Cabezas (I-IV, 1947-49), las dos primeras sin ojos y con las bocas abiertas mostrando desparejos dientes afilados.

Hacia 1950 Bacon dio un nuevo carácter a las figuras humanas que usaba como motivo. Los cuerpos no son tan deformados como anteriormente, y son vistos aislados en espacios indefinidos, como desvaneciéndose tras gruesas y continuas pinceladas verticales, o enmarcados en estructuras geométricas formadas por delgadas líneas de color. Otras figuras están ubicadas sobre o dentro de estructuras circulares que parecen escenas de teatro. El ambiente de las obras es tenso, como en el prolegómeno de una situación violenta, o durante una catástrofe. Estudio del cuerpo humano (1949), Estudio según Velázquez (1950), Estudio de desnudo (1951), Estudio para desnudo agachado (1952) y Dos figuras (1953), tienen esas características.

LAS FUENTES. El estudio de las obras de los años 50 revela un Bacon continuamente a la búsqueda de estímulos visuales, de los más disparatados orígenes, que pudieran activar los mecanismos del proceso creador. Entre las fuentes de inspiración más importantes están las reproducciones de obras de arte de distintos períodos y procedencias, e imágenes tomadas de los medios de comunicación, ya fueran fotografías o ilustraciones, material que amontonaba compulsivamente en sus talleres (ver recuadro). Pero Bacon no copiaba las imágenes que usaba como punto de partida, sino que las deformaba, las combinaba, y, lo más importante, les daba nuevos significados.

Entre las referencias más evidentes, ya clásicas, relacionadas a imágenes tomadas de la historia del arte, se cuentan la relación entre la mencionada pintura y obras de Rembrandt y Chaïm Soutine, con similares motivos de medias reses colgadas, así como entre Estudio según retrato del Papa Inocencio X de Velázquez (1953) y Retrato del Papa Inocencio X (1650) de Velázquez.

Pero las relaciones entre las obras y las fuentes no son lineales y excluyentes, sino que en muchos casos se pueden "descubrir" varias influencias simultáneas. Las bocas abiertas de los personajes de Bacon en las dos últimas obras mencionadas tienen relación con el personaje de la enfermera del Acorazado Potemkin, que emite un grito de dolor al ser herida en un ojo cuando le rompen los lentes. La figura de la enfermera volvió a aparecer como motivo en Estudio para la enfermera del Acorazado Potemkin (1957). En los años 80 Bacon se inspiró en obras de Jean-Auguste Dominique Ingres, influencia que es explícita en los títulos de Edipo y la esfinge según Ingres (1983) y Estudio del cuerpo humano según Ingres (1984).

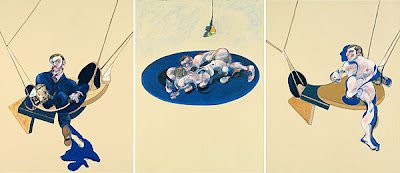

Otra de las fuentes más conocidas de Bacon es el libro de Eadweard Muybridge La figura humana en movimiento (1887), una recopilación de series de fotografías de personas realizando distintos movimientos, tomadas con intervalos regulares, y en algunos casos simultáneamente de dos o tres ángulos diferentes. Una serie con dos luchadores desnudos, que ejecutan movimientos de lucha libre, fue especialmente atractiva para Bacon, ya que le sirvió de base para obras como Dos figuras (1953), Dos figuras en el césped (1954), Figuras en un paisaje (1957), y las partes centrales de los trípticos Tres estudios para figuras en una cama (1972) y Tríptico (1991). En las obras la interacción de los dos hombres desnudos es ambigua, ya que puede ser interpretada como lucha o como acto sexual.

Un artista especialmente significativo para Bacon fue Miguel Ángel, de quien prefirió los llamados ignudi, los musculosos jóvenes desnudos que pintó -sin ninguna justificación programática- en la base de las escenas del techo de la Capilla Sixtina. El cruce de referencias es tal que el propio Bacon afirmó en una entrevista: "Muybridge y Miguel Ángel se me mezclan en la cabeza".

LA CRÍTICA. Bacon no tenía mayor interés en la opinión que los críticos emitían sobre su quehacer artístico. Entre otras cosas expresó: "Si prestara atención a lo que dicen los críticos, no trabajaría nunca" y "Por supuesto, es verdad, hay muy pocas personas que podrían ayudarme con su crítica". La visión sobre su obra varió según los contextos y las épocas, pero a grandes rasgos se puede decir que el temprano interés que despertó en Inglaterra no fue correspondido por los círculos artísticos de Estados Unidos. Al carácter revulsivo de su pintura, se sumó la condición homosexual de Bacon, asunto que, al ser evitado como tema central en los análisis sobre su obra, dificultó su comprensión. Estos obstáculos desaparecieron recién durante los años 80, con la consolidación de las teorías feministas, los estudios queer (estética gay), y la creciente aceptación de la diversidad sexual.

En el catálogo de la reciente exposición del Metropolitan Museum, Gary Tinterow publicó un texto en el que analiza la relación entre la obra de Bacon y la crítica. En un principio, a partir de fines de los años 40, el arte de Bacon fue considerado profundamente europeo, especialmente visto en el contexto de los años inmediatamente posteriores al fin de la Segunda Guerra Mundial. El poder del imaginario baconiano, el horror a lo estático, y un cierto fatalismo, fueron destacados por críticos ingleses como David Sylvester, Robert Melville y Wyndham Lewis.

En cambio, los críticos de Estados Unidos consideraron su obra demasiado figurativa y narrativa, opuesta en su concepción al allí entonces dominante expresionismo abstracto, fuertemente impulsado por el influyente teórico Clement Greenberg. En ese contexto fue problemática la conexión religiosa de las imágenes de Bacon, que revelaban una incómoda visión "impía" de la tradición cristiana.

El interés por Bacon comenzó a generalizarse a partir de comienzos de los años 60, coincidiendo con dos importantes exposiciones de su obra realizadas en la Tate Gallery de Londres en 1962 y el Guggenheim Museum de Nueva York en 1963. Poco después Bacon conoció a Michel Leiris, intelectual que había tenido fuertes lazos con el movimiento surrealista, y que se convirtió en uno de los principales críticos e impulsores de su pintura.

A partir de una gran retrospectiva realizada en el Grand Palais de París en 1971, Bacon comenzó a ser considerado uno de los grandes maestros de la pintura europea contemporánea. Ese mismo año John Russell publicó Francis Bacon, uno de los principales referentes de la literatura sobre el pintor. Otra publicación importante para el estudio de los mecanismos creativos de Bacon fue Interviews with Francis Bacon, publicado por David Sylvester en 1975.

AMIGAS Y AMANTES. Hacia 1960 Bacon imprimió un nuevo giro a su pintura. La figura humana continuó siendo su motivo principal, pero pasó de crear figuras anónimas a retratar a personas de su entorno, tanto amigas y amigos como amantes. Pero el cambio en el carácter del motivo no lo llevó a trabajar directamente con los modelos, sino que continuó con su método de basarse en fotografías, esta vez de los retratados. En 1961 encargó a su amigo John Deakin, fotógrafo de la revista Vogue, que tomara fotografías de sus amigos para usarlas como fuentes.

Los retratos nunca serían realistas, sino basados en deformaciones evocativas, productos de una ambivalencia que era una de las formas de "caminar al borde del abismo". Bacon rompió con la tradición realista del género del retrato, que desde el Renacimiento fue considerado un reflejo de una realidad exterior a la que se puede acceder objetivamente, y propuso en cambio una suerte de "retrato interior". Los retratos están cargados de sexualidad, con la expresión del deseo y la excitación como temas centrales.

De su grupo de amigas, las que Bacon retrató con más frecuencia fueron Isabel Rawsthorne y Henrietta Moraes. La primera era pintora, musa y modelo de artistas (entre otros Jacob Epstein, Picasso y Giacometti), en cuya compañía Bacon acostumbraba beber. Pintó Retrato de Isabel Rawsthorne (1966) y Retrato de Isabel Rawsthorne parada en una calle en Soho (1967), inspirado en fotografías de Deakin. También pintó Tres estudios de Isabel Rawsthorne (1967), con tres retratos simultáneos (uno de ellos una pintura clavada en una pared), obra que plantea la diferencia entre la realidad y su representación. Henrietta Moraes bebía mucho, consumía distintas drogas, y frecuentaba los bares de Chelsea, al igual que Bacon. Una fotografía tomada por Deakin, en la que se la ve acostada desnuda en una cama, sirvió de fuente para Retrato de Henrietta Moraes (1966).

Bacon también pintó numerosos retratos de sus amantes. No retrató a Peter Lacy, ex piloto de la RAF con quien mantuvo una intensa y violenta relación entre 1952 y 1958, debido a que en esa época las personas de sus motivos eran anónimas. En cambio los retratos de George Dyer, un joven ladrón al que sorprendió in fraganti una noche de 1963 robando en su casa (y que fue su amante a partir de entonces), ocupan un lugar central en el corpus de la obra que creó durante los años 60. Pintó una larga serie de estudios de cabezas de Dyer, y varios retratos entre los que se cuentan Retrato de George Dyer andando en bicicleta (1966) y Estudio de George Dyer en un espejo (1968). Dyer se suicidó en un hotel de París en 1971, el día antes de la inauguración de la retrospectiva de Bacon en el Grand Palais. Luego de la muerte de Dyer, Bacon pintó varios trípticos relacionados a su ex amante, entre otros Tríptico - En memoria de George Dyer (1971) y Tríptico - Agosto 1972. En 1976 conoció a su último amante estable, John Edwards, un joven con el que comenzó una larga relación de tipo paternal, de quien también pintó varios retratos.

Otros modelos masculinos de Bacon fueron su colega Lucian Freud, a quien había conocido ya en 1943, y amigos como Peter Beard y Michel Leiris. Estos aparecen en retratos individuales o en trípticos, un formato que Bacon iba a utilizar tanto para dar tres distintas versiones de la misma persona, como para conectar entre sí las figuras de los retratados. Este último es el caso de Tres retratos - Retrato póstumo de George Dyer, Autorretrato, Retrato de Lucian Freud (1973), en el que Bacon agregó, en las telas con los retratos de Dyer y Freud, dos pequeños autorretratos ilusoriamente clavados en la pared, con lo que se "incluyó" tras las figuras del ex amante y el colega.

VARIACIONES FORMALES. En algunas de las obras individuales y trípticos que Bacon pintó a partir de comienzos de los años 70 es evidente un nuevo planteo espacial: los elementos en que las figuras humanas se apoyaban, ya fueran sillas o camas, fueron sustituidas por rectángulos negros que sugieren ventanas u otras aberturas, y que funcionan como fondo o lugar de "acción" de las figuras. Algunos ejemplos son Figura en movimiento (1985), Retrato de John Edwards (1988), Tríptico, mayo-junio 1973 y Tríptico, Marzo 1974, así como los mencionados Tríptico-agosto 1972 y Tríptico (1991).

En cuanto a los motivos, hacia 1980 Bacon comenzó a realizar obras que no incluían la figura humana, la que había sido central en su obra durante cuatro décadas. En el papel protagónico se encuentran elementos como arena, césped, agua y sangre, los que se expanden sobre la superficie de las telas. Sin embargo, tanto los motivos estáticos, en Paisaje (1978), Duna de arena (1983) y Sangre en el pavimento (1988), como los que imitan movimiento, en Agua de una canilla abierta (1982) y Chorro de agua (1988), evocan la presencia humana. Otra fuente de motivos a la que recurrió durante diferentes etapas de su carrera fueron textos literarios de la más diversa procedencia, lo que resultó en obras como Tríptico - Inspirado por el poema `Sweeney Agonistes` de T.S. Eliot (1967) y Tríptico - Inspirado por la Orestíada de Esquilo (1981).

En abril de 1992 Bacon, contrariando la opinión de su médico, viajó una vez más a Madrid a visitar a José Capello, con quien mantuvo una de sus últimas relaciones conocidas. Aquejado de neumonía, la que se agravó por el asma, fue hospitalizado. A los pocos días murió muy cerca del Museo del Prado, donde recientemente sus obras han sido expuestas junto a las de su admirado Velázquez.

Arqueología pictórica

UNA SERIE de fotografías de los talleres en que Bacon trabajó durante diferentes épocas muestran un caótico amontonamiento de pinceles, tubos de color, paletas, un espejo y algunos muebles desvencijados, todo mezclado con material gráfico que el artista apilaba, amontonaba en cajas de cartón, e incluso esparcía por el suelo. Hojas de periódicos, libros, revistas y fotografías aparecen en un desorden bestial, doblados, arrugados, rasgados, recortados y manchados de pintura.

Cosas del taller

LUEGO DE dejar la casa de 7 Cromwell Place en abril de 1951, Bacon vivió durante una década en casas de amigos y colegas. Durante un par de años el pintor Rodrigo Moynihan le prestó su taller, donde Bacon fue fotografiado por Henri Cartier-Bresson. En 1955 se mudó a un apartamento en 9 Overstrand Mansions, Battersea, donde una pareja de amigos le ofreció lugar. Finalmente, en 1961, se mudó a 7 Reece Mews; allí tuvo su vivienda y taller hasta su muerte en 1992. Cada mudanza significaba un trasiego de libros y recortes.

Hay numerosos testimonios sobre la negativa de Bacon a permitir el acceso a sus talleres. Cuando recibía a alguien, no permitía que nadie tocara nada. El ocultamiento de los materiales gráficos se debía a que eran "documentos de trabajo", sobre los que mantenía absoluto secreto. En la vivienda de Reece Mews usó una pequeña habitación de 6 x 4 metros como taller durante más de treinta años. A pesar de que regularmente realizaba limpiezas (cuando era superado por el amontonamiento), dejó tras de sí miles de piezas de material.

Luego de la muerte de Bacon en 1992, el taller permaneció cerrado hasta 1996, cuando John Edwards (designado heredero por el artista) invitó a los expertos Brian Clarke y David Sylvester a revisar el material. Dos años más tarde Edwards donó el taller completo, con todo su contenido -más de siete mil objetos- a la galería municipal de Dublín The Hugh Lane, un homenaje a la ciudad natal de Bacon. El taller fue estudiado como un sitio arqueológico, con mediciones y dibujos alzados previos a la clasificación objeto por objeto del material, el que finalmente fue trasladado a Dublín, donde se reconstruyó el taller.

Parte del material ahora perteneciente a The Hugh Lane fue clasificado y publicado por Martin Harrison en Francis Bacon, Archivos privados. El autor se rigió por dos principios: la diversidad, para mostrar la amplitud del archivo visual de Bacon, y la precisión en la identificación de procedencia y fecha de los materiales, los que fueron estudiados uno por uno con minuciosidad.

El material gráfico publicado muestra que algunos objetos están casualmente manchados, pero la mayoría fue transformada por Bacon de distintas formas: dobló, recortó, e incluso pintó partes de reproducciones y fotografías. Los materiales intervenidos funcionaban como bocetos, estudios preliminares para figuras que el artista iba a incluir en sus obras. La nueva información sobre las fuentes de Bacon es enorme. A las ya conocidas, como pinturas de Velázquez y fotografías de Muybridge, se le suman una serie de nuevas fuentes.

Harrison menciona dos obras sobre las que el estudio del contenido del taller arrojó nueva luz. En el panel izquierdo de un tríptico de 1982 (que luego fue desmantelado, y por lo tanto sin título), un pollo desplumado está colgado por las patas sobre una figura tendida en una tarima. La fuente para la figura del pollo resultó ser un libro de cocina, The Cook Book, publicado por Terence y Caroline Conran en Londres en 1980. En la página 84, en el capítulo Poultry (Aves), se ve una ilustración de cinco aves desplumadas colgadas en tamaño decreciente. La del medio tiene exactamente la forma del pollo que Bacon pintó en su obra. La información fue completada aun con otro dato: la amistad entre Bacon y Terence Conran, quien en 1987 abrió el restaurante Bibendum, luego uno de los lugares favoritos del pintor.

La segunda obra estudiada por Harrison es Esfinge - Retrato de Muriel Belcher (1979), en la que Bacon combinó imágenes de distintas procedencias. La cabeza de la esfinge es un retrato de una de las más íntimas amigas de Bacon: Muriel Belcher, dueña de la coctelería Colony Room, que el pintor frecuentaba en los años 40. La fuente fue una fotografía tomada por John Timbers en 1975, la que Bacon intervino aislando con pintura blanca la cabeza de Belcher, para así estudiar mejor su forma. La apariencia de las garras y parte del cuerpo de la esfinge provienen de una fotografía de la bailarina Marcia Haydée, ilustración de una nota sobre danza publicada en The Observer el 4 de junio de 1978, que Bacon rasgó de la página y guardó. En la obra, la garra derecha de la esfinge descansa sobre una forma que semeja un papel con letras, una posible referencia a la fuente.

Sobre el material que sobrevivió a Bacon, Harrison escribió: "Apenas nos hemos internado en la telaraña de pistas que nos dejó". A lo que Barbara Dawson, directora de The Hugh Lane, agregó: "Entrar en el estudio de Francis Bacon fue como asomarse al interior de la mente del artista".

FRANCIS BACON, ARCHIVOS PRIVADOS, de Martin Harrison. La Fábrica Editorial. Madrid, 2009. Distribuye Océano, 224 págs.

Volver a Bacon

María Sánchez

Cuando tenía 16 años, me topé con una exposición de un artista llamado Francis Bacon en un museo de Dublín. No recuerdo que me gustara, en el sentido de lo que entonces yo consideraba bello, pero sí que me impactaron dos cosas: la crueldad que transmitían las obras y el desorden absoluto del estudio del pintor, que había sido reconstruido en una sala del museo.

Creía haber olvidado esto cuando me encontré con cientos de retratos del Papa (Heads VI) llenando de gritos los muros del metro de Madrid, cuando media España hablaba de Bacon como si fuera el vecino del quinto piso, y cuando, un mes de marzo, las colas daban la vuelta al Museo del Prado. Bacon llegó a Madrid como llega el circo a la ciudad.

En esta ocasión volví a Bacon con otros conocimientos, otras expectativas, otros gustos. Sin embargo, hasta que no estuve delante de los cuadros no recordé aquel sentimiento. Volví a Bacon, volví a Irlanda y a mí misma; porque Bacon es esa bestia que hay dentro de cada persona y que tanto asusta descubrir.

Bacon es uno de esos artistas que verifican la frase "no es lo mismo la obra que la reproducción de la obra". En los libros, en los carteles del metro, en la televisión, en ningún medio provocan esa misma emoción.

Los cuadros sangrantes y calientes se contraponen con los fríos gritos que desgarran el lienzo en líneas verticales. La poca pintura expandida con fiereza enjaula las figuras en la tela y las retuerce hasta la locura. Bestialidad, contorsión, corporeidad y tensión. Impresión y expresión. Respiración y expiración.

NOTA: María Sánchez (n. 1986) es española, y realiza una pasantía de posgrado en El País Cultural.